As our office gathered virtually to plan for this semester, we found ourselves inspired by several new initiatives for engaging more with all of you during a time when even those of us who are on campus this semester might be feeling isolated from each other. One of the ideas we discussed in our brainstorming sessions was to create a place where we as a community can honor our personal queer heroes or Queeroes as we’re calling them. Our communities—as students and employees at Harvard, as people across the spectrum of queer identity, as human beings living and working together—these networks are built on a long history of people who just like us found themselves fighting for the rights of others, fighting for the right to be their authentic selves, and fighting to simply live joyously.

We boiled all of our discussions into a prompt that we want to open up to all of you:

Of the many queer people across history, of both large and small-scale impact, who inspires you? Who is your Queer Hero?

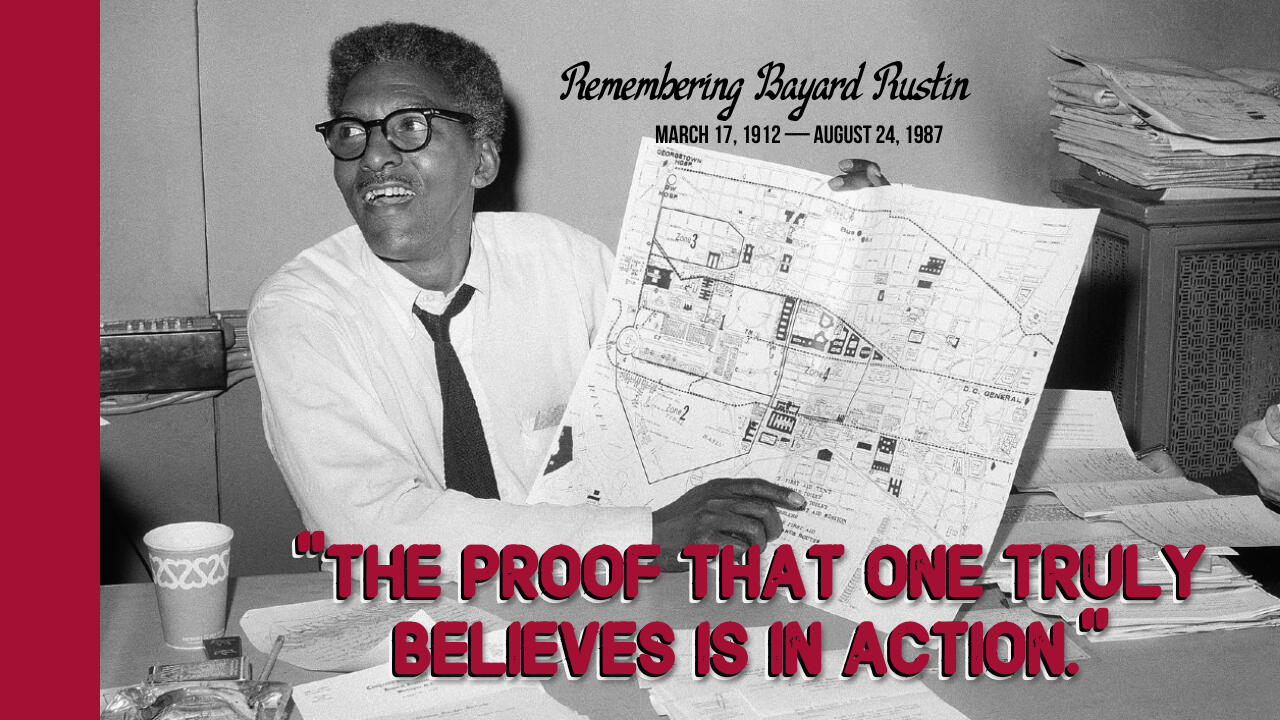

Our colleague Stone Cox was quick to answer; his Queero is Bayard Rustin, a gay civil rights leader responsible for the organization of the March on Washington in 1963, a historic event that we know as the stage for Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech, a moment that perhaps even slightly overshadows the colossal efforts of the many organizers who got an estimate of at least 250,000 people to take the risk of mass mobilization. Stone invited us to do some research into Bayard’s life as we envisioned what this project might become. In taking this invitation, we not only got to learn about someone who is a source of inspiration for our friend, but also found ourselves inspired by Bayard’s unwavering commitment to risking his own safety and popularity among his co-organizers in the fight for justice and equality.

In our search for information about Rustin’s life, we learned about his childhood in which he was raised with the Quaker value of nonviolence by a grandmother who herself was a fighter for social rights. We learned about the countless hours of planning that he put into the organization of the march itself, ranging from figuring out how many bathrooms a quarter of a million people might need to figuring out bus schedules to succinctly drafting the goals that would define the movement as a whole.

We learned that throughout his organizing and fight for justice, Bayard faced constant suspicion from and defamation by allies and enemies alike for his politics and open homosexuality. We learned about his arrests and imprisonment. He would not be deterred. We learned about his unwavering commitment to the task of fighting no matter how often his ego might have been bruised in the process, even when other civil rights leaders were cautioned to distance themself from him. Perhaps it is not surprising that Rustin’s name does not appear in our textbooks, even though he is the one who read out the 10 demandsthat MLK and nine other civil rights leaders presented to President Kennedy after the famous speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. We were struck by how, if you listen to recordings of the speakers from the day, Rustin asked for the assent of everyone gathered there that day for each of these demands and how these demands are not so different from the calls for social justice that we hear in the present. It is a sobering if not altogether disappointing realization. Too often, even though we have always been here, queer people are pushed to the margins of the history that they were instrumental in setting in motion.

In the image at the start of this reflection on Rustin’s life, we quoted him saying the “proof that one truly believes is in action.” Whether right or wrong on all of his beliefs, it seems that he was someone who stuck to his convictions and looked for solutions. It seems he was someone who fought for what he thought was right, for what he thought would help people around him. It looks as though he was someone who always looked for alternative solutions when faced with a seemingly insurmountable challenge.

As we look forward to this semester, we are reminded that Bayard began his organizing for civil rights when he was a college student and we are imagining how some of you reading this right now might one day be a part of changing the world as he did. We wonder what a world where we all grew up celebrating people like Rustin regardless of (or perhaps for) his sexuality might look like. To that end, if there is a queer hero who inspires you and that you want to help commemorate, we invite you to email us at BGLTQ@fas.harvard.edu and be a part of our Queeroes project. You are welcome to commemorate them in essay format as we did or in any medium of your choosing. As we get submissions, we will be posting them online where we hope they can continue inspiring the coming generations that will pass through our QuOffice.